By Andrea Brás

According to Access Now’s Shutdown Tracker Optimization Project (STOP), the number of recorded Internet shutdowns has spiked from 75 in 2016 to 188 in 2018, with the majority of these affecting users in Asia and Africa.

Recently, Zimbabwean authorities shut down the internet after price hikes on fuel costs brought people to the streets — leading to a crackdown on protesters and the first observed complete internet shutdown in the nation’s history. Disruption to Internet services in the country ended on January 21st after Zimbabwe’s High Court ruled the shutdowns illegal; however, Information, Publicity and Broadcasting Services deputy minister Energy Mutodi recently stated that the government would not hesitate to implement these measures again.

After seeing VPN searches shoot up by 1500%, we spoke with our partners in Zimbabwe to learn more about how VPNs are being talked about and shared, and what role memes can play in popularizing their everyday use.

a Total Internet Shutdown: ‘We never saw it coming’

This is not the first time that Zimbabwe has experienced intentional disruptions to their Internet service. In 2016, while Robert Mugabe was still in power, protesters took to the streets en masse to voice their discontent over the country’s economic situation and were met with the shutdown of social media sites like WhatsApp. Because of this previous experience, many people expected a partial shutdown but were unprepared for the more drastic measures taken by the current government. According to Sean Ndlovu, co-founder of the Center for Innovation & Technology and one of Localization Lab’s contributors, when the government implemented a total Internet shutdown, he was caught off guard:

“When the call for shutdowns started, some of us in the digital security sector started telling people to prepare. But in our minds we were thinking it would be something like social media, not the total shutdown of the Internet. The population didn’t really expect that the Internet would shutdown, because I remember people were encouraging others to download Psiphon and other VPNs, and everyone said ‘No, nothing is going to happen. The president won’t mess up his reputation for this’ You know, the regular rhetoric that everything would go according to plan, but, alas, they did turn off the Internet.”

For Arthur Gwagwa, a Senior Research Fellow at Strathmore University, the sentiment of surprise was the same:

“The president has been giving a face to the international community, making them think that he wouldn’t do something like this -- so we never saw it coming. Even during the 2016 protests the internet wasn’t totally shut down like this.”

An Internet shutdown is defined as “an intentional disruption of internet or electronic communications, rendering them inaccessible or effectively unusable, for a specific population or within a location, often to exert control over the flow of information.” This can mean, Internet throttling (or intentionally slowing down Internet bandwidth so as to make it basically unusable), partial Internet shutdowns (like the blocking of specific social media sites), and total Internet shutdowns (also known as blackouts or kill switches). According to a report by OONI Probe, in the case of Zimbabwe, the government implemented all of these tactics -- starting with throttling, then moving on to blocking social media sites like Twitter and WhatsApp, until they finally shut the internet down completely.

Starting on January 15th until January 21st, Zimbabwe experienced some form of disruption to access, with the most drastic kill switch measures indicated as taking place during parts of the day on the 16th and the 18th. According to Gwagwa:

“The shutdown happened gradually. Social media and apps shut down then opened up. When it was open for a little while, this allowed people to communicate with other activists and Zimbabweans living abroad. By potentially trying to protect their international reputation, the government hesitated on a total shutdown and turned the Internet on and off. This window gave Zimbabweans the opportunity to talk to each other and find out what was really going on.”

However, despite Zimbabweans sharing information during windows of time when the Internet was open, misinformation about what was happening inside the country was being spread, most notably by Deputy Minister Energy Mutodi. For Ndlovu:

“The average user didn’t understand what was going on in the beginning. The Deputy Minister of Information came out on national TV saying that the internet was congested which is why it was slow. People started sharing that message… so now you see that there were two narratives. [The government] was peddling their own propaganda and then you have those that were saying, no but the internet is shut down because of A, B, C and D.”

Digital security trainer and LocLab Shona language coordinator Chido Musodza felt that it was impossible for most people to believe the government rhetoric after one of the major Internet Service Providers sent out messages to its clients admitting that they were blocking the Internet:

“We received a text message from Econet telling us that they received a directive from the government to shut down the Internet. After we heard the message from the Minister of Information on national TV saying that it was congestion, we just thought “Who is going to believe that!”

‘VPN Searches in Zimbabwe surge by 1,500%’

According to UK-based service BestVPN.com, VPN searches by Zimbabweans surged by 1,500% during the recent shutdown. This happened in tandem with civil society organizations advocating for VPN use from trusted sources on Twitter and other social media sites:

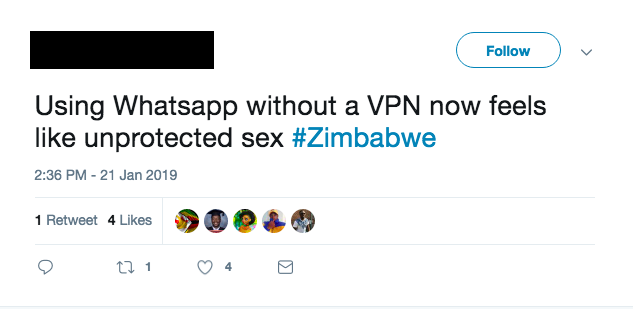

Both inside and outside of Zimbabwe, people began sending VPN suggestions to users via social media. The popularity of VPNs during the shutdown can be seen by the ubiquitous number of tweets, memes, and messages talking about VPNs in the country:

Translation from Shona:

Using WhatsApp and Facebook via a VPN is no different to attending class over the weekend.

There will be no one to chat with!

Although interest in VPNs was on the rise during the shutdown, accessing them posed a different problem because of existing limitations related to the country’s Internet infrastructure. Zimbabwe ranks 125 out of 200 countries for broadband speed and its users pay some of the highest prices for data packages in Africa — making downloads both costly and slow. In response, many users turned to popular file sharing app SHAREit, which works via Wi-Fi direct. When people were unable to download new apps during the shutdown, those who already had VPNs on their phone were able to use SHAREit to send their VPNs to other community members. Gwagwa was one user who took advantage of this:

“We are such a communal nation -- we are always communicating with each other. Here everyone is everyone’s son or daughter. When the shutdown happened, I went around my neighbourhood and shared a VPN I trusted with my community.”

However, despite people trying to push for vetted VPNs, it would seem that a general lack of understanding about how VPNs work and misinformation about the dangers associated with VPNs caused confusion during the most critical moments of the shutdown. According to Ndlovu:

“People were advocating for VPNs via social media. First via Twitter, then Facebook, then WhatsApp. But when it came to VPNs there was a problem -- most people were just jumping on any VPN that they found in the Playstore or the App Store. So that became a challenge because people in the digital security sphere were pushing for trusted VPNs like Psiphon or Tunnelbear, but then people were out there saying that they were using this and that. After the total Internet shutdown, people didn’t understand that even if you have a VPN you won’t go through because you have no access to the outside world. So again, people are totally confused because they thought that with a VPN you could access the Internet even if it was totally shut off, so there was a bit of misconception going on there.”

Unfortunately, these misconceptions can lead to real digital security issues -- especially when VPNs are being downloaded from untrustworthy sites. It is not unheard of for scams masquerading as digital security apps to lure unsuspecting users into giving up personal and private information. In a context like Zimbabwe’s, when people were urgently trying to get back online, the risk that people could download an unsecure VPN is much higher. This was the case for some of Musodza’s contacts:

“In some situations we realized that people had up to 21 VPNs on their phone. And none of them were the recommended ones. We kept trying to push for trusted and recommended VPNs like Psiphon and TunnelBear. But people were downloading all sorts of things”

Screenshot of phone with VPN downloads. Courtesy of Chido Musodza.

According to Ndlovu, the answer lies in making digital security education more readily available:

“We need literature. We need a campaign to tell people what VPNs are. When you are trying to explain a VPN, often times, no matter how many diagrams you draw, people won’t quite understand. But now, in this context, people are beginning to understand. But, we need to educate them more about the advantages of a VPN, what it is and how to use it. We also need people to know that it is not just about circumventing government restrictions, but it’s also for your own privacy. That’s the message that we need to spread to people.”

Ndlovu thinks that this message should include the importance of making VPNs a part of Zimbabweans everyday lives, and the first obstacle to overcome is making sure that people don’t delete their VPNs after the shutdown ends. Phone memory is often an issue for Zimbabweans, and due to limited space, people need to delete unused apps off of their phones. Gwagwa is pushing for digital security trainers and Internet researchers to take advantage of the current situation and raise greater awareness around VPN use:

“We need to take advantage of the current mood in the country. Now, it is not an option. VPNs should be the first thing people see on their screen. Some people are going to delete the VPN because of phone space. We need to preach the gospel more.”

For Gwagwa, part of the solution may rest on social media -- more specifically with jokes and memes.

“We need to make tools more accessible. Make them easier to understand. Memes have been raising awareness about VPNs because of jokes. They can help by simplifying it into better language. Zimbabweans have a great sense of humor. Even during moments of adversity, we love to laugh.”

According to An Xiao Mina, technologist and author of Memes to Movements, harnessing the power of memes and jokes to spread information about VPN use is a viable strategy to get people interested in this technology:

“Memes are a critical vector for spreading information—for better or worse—through digital media. So it makes sense that information is being spread through memes, and the best way to do that is to create engaging and humorous content that will get people's attention and hopefully drive them to good VPN adoption.

The risk, of course, is that memes can also spread misinformation about VPNs. The most effective memetic methods, then, combine the humor and engagement of memes with other forms of education and engagement about proper VPN usage.”

If done the right way, humor may just be the key to getting more people to download and use secure and vetted VPN apps. But as we saw during the Zimbabwe shutdown, this still won’t help when governments decide to turn off the Internet. In these cases, Ndlovu says we may have to look to the Internet Freedom community for help:

“We need a safety guide with offline solutions for total Internet shutdowns that we can trust and use so that people don’t just jump on any tool that they hear about on the Internet. I think we are going to have more protests in our future, so that means the potential for more shutdowns [in Zimbabwe] is high and we need these solutions now.”