Beyond Translation: Localization Sprints for Sustainable Tech Adoption

Thai Localization Sprint Participants.

By Erin McConnell

“I wish to see [human rights defenders who] are at risk, especially in rural areas, using these tools as efficiently as urban-based activists. Thanks Localization Sprint for making these apps more accessible!”

- Thai Localization Sprint Participant

In June 2019, Localization Lab facilitated a digital security workshop in Thailand with Internews and a number of amazing, local civil society groups. The main goal was to collaboratively localize and provide user feedback for four digital security tools that the Thai participants had identified: Mailvelope, Tor Browser, TunnelBear and KeePassXC.

With only 5 days, the Localization Sprint had lofty goals:

Support freedom of speech online;

Collect qualitative feedback on the tools from the community;

Give Thai users ownership over digital security tools to ensure sustained use and engagement; and

Strengthen the existing network of Thai localizers and users of digital security tools.

Participants joined from a diverse set of backgrounds and several had never heard of these tools before. A localization sprint is inherently collaborative. People with more technical experience helped those with less, and everyone put forth their best effort. It takes considerable work for a small group to translate and review four different applications in five days. And yet the feeling in the room was upbeat - people played their favorite music and felt empowered to use and contribute to these technologies. The process also challenged everyone in the room to think about how normal Thai people could use digital security tools to protect themselves online.

“I really liked this workshop, especially the tool training parts which helped me understand the tools more clearly and understand how - and in which situations - I should use these tools, which I never knew before. These tools are very useful for Thai people and we should help spread their use.”

- Thai Localization Sprint Participant

Sprint participants collaboratively translating. Photo courtesy of Erin McConnell.

Localization and User Feedback: A match made in Pattaya

Incorporating user feedback into the localization process is the perfect opportunity to gain insight into the needs and preferences of users from a diversity of backgrounds.

The sprint participants came with varied technical backgrounds. Some attendees had trained others on several of the tools that were being localized, and others had never used them before. This provided a valuable chance to better understand the user experiences of absolute beginners and more seasoned users of each tool.

To capture some of this feedback, participants were asked to follow and fill out USABLE Tool Task Ranking forms, customized for both Mailvelope and KeePassXC. Participants rated the difficulty and commented on tasks as they walked through steps like creating a keypair and sending encrypted email with Mailvelope, or creating an encrypted password database in KeePassXC.

“Adaptation of marketing tools like these personas are really beneficial. We can use them in our sector [non-profit].”

- Thai Localization Sprint Participant

Snapshot of the Okthanks One Liners available for download on their website.

At the end of each day, after participants had gone through training and localization of the tools, they were given a One Liners form developed by Okthanks to capture concise feedback about the user experience. The One Liners forms glean meaningful information from users about their first impressions of an app and their understanding of its function:

Integrating both of these feedback activities into the localization process - in addition to observations from throughout the day - the sprint documented valuable information about Thai user needs and preferences for all of the projects localized.

Diving into Local Needs: User Stories and Persona Building

The Thai Localization Sprint challenged sprint attendees to imagine different Thai user profiles and their digital security needs and motivations through user story creation and persona building (for example, imagining a middle-aged farmer or a teenage student and their needs.) This helped the participants better understand Tor, its diverse use cases and the large breadth of individuals who could benefit from using it. Particularly with tools like Tor that come with a lot of misconceptions, it is important for users to imagine themselves and others in their networks using the application. It’s imperative that individuals be able to create narratives that resonate with their communities so that they better understand the tools and adopt them when appropriate.

The persona building and user story activities - done in small groups - resulted in very different outputs, drawing from experiences in the human rights sphere and outside of it. The personas and stories highlighted how Tor and other digital security tools are not limited to those in activist or human rights work. Digital security issues are relevant to all and tools like Tor can address the needs of a social media influencer, a land rights activist, or someone who wants to privately used a shared computer or mobile device.

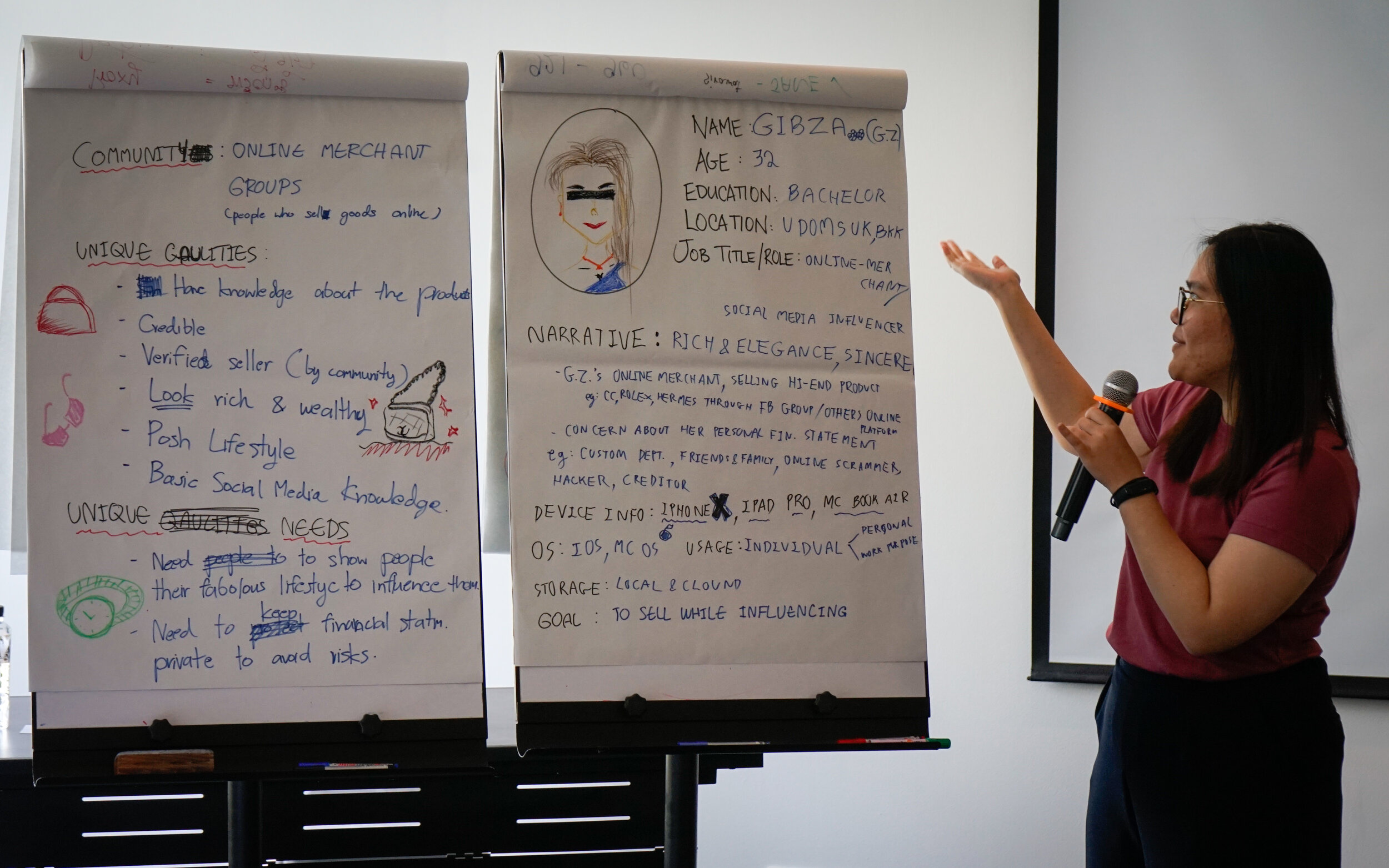

Collaborative user persona activity resulted in two drastically different user profiles. N shares Group 2’s user profile, Gibza.

Imagining Thai User Personas

Persona Builder activity developed by Okthanks. Photo: https://okthanks.com/persona-builder

The Okthanks Persona Builder gamifies the creation of user personas to help organizations and developers explore the security concerns of individuals from different backgrounds and working in different contexts. The activity was used to introduce and explore Thai personas, using USABLE personas as a guide, so that participants could integrate them into their future work.

Following an adapted version of the Persona Builder game, each group determined the name, age, education, location and job title or role of their persona and then picked four more user persona components at random from a shuffled stack of options. Examples of available persona components included: the individual’s unique priorities, the devices and applications they use, their technical strengths and frustrations, information about their connectivity, political dynamics in their region etc.

“We work on digital security in urban areas, and we often forget the limitations and difficulties that those in rural areas are facing. This was a good exercise to look back on these issues.”

- Thai Localization Sprint Participant

Nu Nui, the farmer and land rights activist from the Upper South of Thailand.

Git shares the user persona of community organizer, Nu Nui.

The end result was two drastically different personas. The first user persona, Nu Nui, reflected the experience of participants who worked with land rights issues in Thailand. Nu Nui was a farmer in the Upper South of Thailand who was involved in community organizing around land rights. She had little technical literacy and faced physical threats from corporate developers trying to acquire land. Through the activity, the group identified several digital security threats and needs for Nu Nui and her community, including: secure communications, a panic button application in case of physical threat, secure information storage for legal documents, secure backup, and the ability to delete sensitive content quickly on a mobile device.

The second group imagined a very different persona than Nu Nui. They profiled Gibza, an social media influencer and owner of an online business. Gibza, whose priorities revolve around her physical appearance and social status, would only use Apple devices, which participants noted is a status symbol in Thailand, limiting her to applications for iOS and macOS. One of her key concerns was keeping banking and financial information secure from government and family members to avoid paying import taxes on resale items and to avoid family requesting financial aid. While Gibza had security concerns, any solutions would have to fit seamlessly into her carefully curated image.

Gibza, the social media influencer.

Who is the Thai Tor Browser User?

While many individuals are familiar with the Tor Project, the project’s image remains fraught with myths and misconceptions. Particularly in certain regions, the browser is associated with illegal activity or dismissed as a tool only for those with “something to hide”. To challenge these perceptions and explore the myriad of uses for Tor the group was tasked with creating user stories based on an overview of Tor earlier in the day.

Participants were split into two groups and each received copies of the recently released Tor outreach fliers, which contain user stories focusing on key uses for Tor (anti-censorship, anonymity, privacy). Each group wrote a Tor user story in Thai for a local context which identified an individual, the goal they wanted to achieve and how Tor helped them reach that goal.

User Story 1:

แอ๋ม เป็นสาวพนักงานธนาคารแห่งหนึ่ง แอ๋มสนใจอยากซื้อ Sex Toy แต่จะเซิร์สดูก็กลัวว่าเพื่อนร่วมงานจะรู้ว่าแอ๋มเป็นคนเปิดดู เพราะในออฟฟิศมีฝ่าน ITคอยตรวจสอบการใช้งานอินเทอร์เน็ต บวกกับที่บ้านใช้คอมพิวเตอร์ร่วมกันจึงมองหาเครื่องมือที่ปลอดภัย โดยไม่สามารถระบุ IP Address หรือมีประวัติการใช้งาน แอ๋มบังเอิญได้ดูคลิปของเจ๊ตุ๊ก ซึ่งเป็นนักกิจกรรมผู้หญิงบน Facebook แนะนำให้ใช้ Tor Browser จึงหันมาใช้ Tor Browser ตอนนี้แอ๋มรู้สึกสบายใจค้นหาความรู้ด้าน sex toy อย่างสบายใจและมีความสุข

“Am” is a bank worker who wants to purchase a sex toy for herself online. Since selling sex toys in country A is illegal, there is no sex shop where Am can purchase the toy. However, she’s worried that if she searches or purchases the sex toy with her work’s laptop, the IT staff could trace the traffic and expose her activity. She also cannot use her personal laptop at home since there is only one shared laptop for the whole family. Am wants a tool that would allow her to be anonymous and keep her IP address and search history from being traced. Am saw a clip on Facebook of a woman activist mentioning Tor Browser. She therefore used Tor to search for and purchase a sex toy.

The user story was inspired by the recent doxing of a Thai woman who purchased a sex toy online. According to the group members, when the toy was being delivered, the box was damaged allowing the delivery person to see inside. The delivery person took photos of the contents and the woman’s full name and address and shared them on social media. Participants shared that sexuality is still very taboo in Thailand, and particularly for women. Being exposed purchasing a sex toy can have serious social and professional ramifications.

User Story #2. Building Tor User Stories for a Thai context.

The second user story was also born out of a real-life situation in which an activist was arrested after online political activity was traced back to him through his IP address. When sharing these user stories, it was important to remind participants that logging into accounts or making purchases using identifying information - even via Tor - affects security and anonymity significantly.

User Story 2:

น้องยีราฟเป็นนักศึกษาและนักกิจกรรมที่อยากจะเริ่มรณรงค์เรื่องความโปร่งใสและเป็นธรรมของการเลือกตั้งบนโซเซียลมีเดีย แต่ก่อนหน้านี้ ยีราฟอ่านข่าวพบว่ามีคนเคยโดนแจ้งข้อหาจากการวิพากวิจารณ์ กกต. บนโลกออนไลน์ โดยใช้ IP Address เป็นหลักฐาน น้องยีราฟจึงมองหาเครื่องมือที่ปลอดภัยที่สามารถรณรงค์ได้โดยไม่ถูกตามจับจาก IP Address เพื่อนนักกิจกรรมหลายคนจึงแนะนำให้ยีราฟใช้ Tor Browser ยีราฟจึงหันมาใช้ Tor แทนเบราว์เซอร์ทั่วไป ยีราฟรู้สึกแสดงความคิดเห็นเสรีและปลอดภัยมากขึ้น

“Giraffe” is a student activist who wants to create an online campaign on transparency of country B’s national election. However, Giraffe read a news article about a case in which a person shared an online petition to dissolve country B’s Election Commission because the election was a fraud, and that person was then arrested. The police arrested that person by tracing their IP address. Giraffe is worried that she could be arrested if she does online campaigning. Therefore, she’s looking for a tool that would help her do an online campaign without sharing her IP address. Her activist friends recommended she use Tor Browser, instead of normal browser. Giraffe used Tor and felt more comfortable to express her opinion online and mobilize her campaign.

Localization as a Tool for Education, Feedback and Outreach

Localization Sprints are not only a way to efficiently localize technologies. They are an opportunity to introduce new technologies and technical concepts, provide culturally & regionally specific feedback for developers, create stronger regional networks, and devise outreach and localized marketing strategies for sharing localized tools with the community. Together these elements can lead to more informed and sustained adoption of technologies as sprint participants better understand the tools they are using, have them available in their preferred language, identify clearer lines of communication with developers, and have more ownership over the tools as contributors to them themselves.

“I have more understanding of the concepts behind the tools. I've also learned that these tools are important in daily life and we can use them in real life.”

- Thai Localization Sprint Participant

If you are interested in learning more about Localization Sprints or would like to coordinate one, you can connect with Localization Lab via localizationlab.org or Twitter.